It is often mistakenly thought that Bristol’s aerospace industry was all about its civil and military aircraft, however, it was missiles which saved Filton’s financial fortunes in the post-war era. For the 70th anniversary of the British Aircraft Corporation's Guided Weapons Division’s foundation Brian Blestowe, former design engineer with BAC, wrote about the history of the Division for publication in the Bristol Times dated 30th April 2019.

When the Allies occupied Germany at the end of the Second World War, they discovered the Nazis had made great strides in the design of aerial weapons that were unmanned in flight. The V1 and V2 weapons had been put into mass production and used mainly against the UK, causing the deaths of over 8,000 residents in the London area.

The Allies also found that the Nazis had made considerable progress in the production of unmanned flying weapons intended to destroy attacking aircraft.

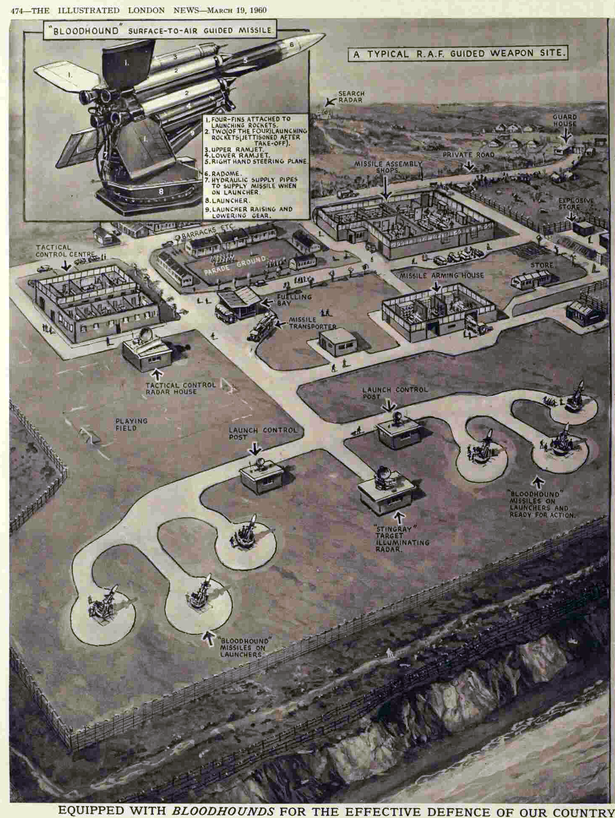

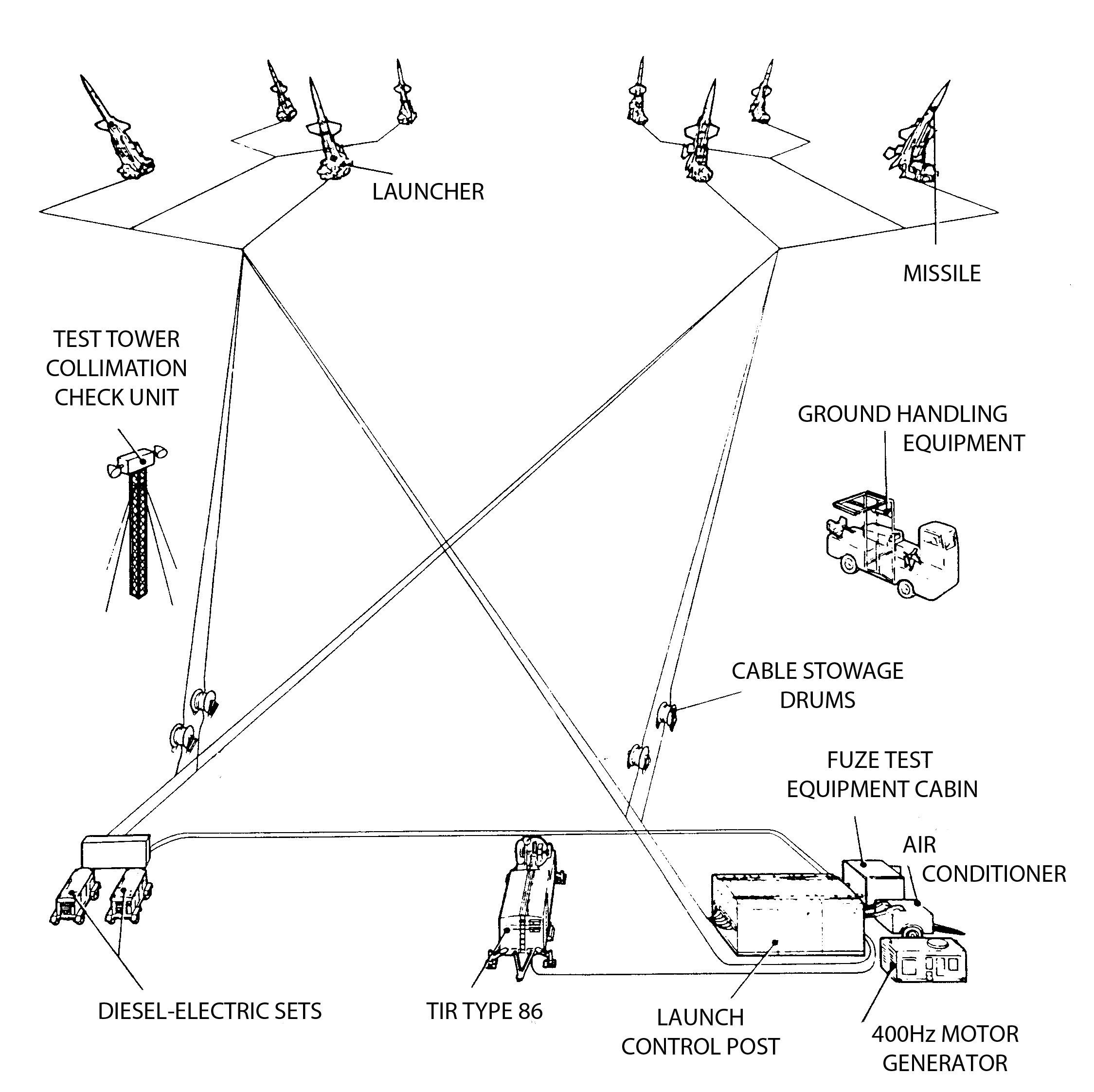

Shortly after the end of the war the UK government recognised the threat and decided to organise the aircraft industry and the new defence-orientated electronics industry that had grown up during the war, into businesses capable of undertaking this new and technically-advanced activity.

Seventy years ago, on April 28, 1949, a group of Ministry of Supply officials and representatives of the Bristol Aeroplane Company (BAC) met in secret in a London Thames-side building that would one day become the HQ of MI5. On the agenda was the growing need for a ground-to-air missile capable of intercepting and destroying the USSR’s high-flying nuclear-armed bombers, then posing an increasing threat as the Cold War intensified.

Archibald Russell, later Concorde’s chief designer, is recorded in that meeting’s minutes as saying that his company’s long-term view was that guided weapons should become their main military effort. Little did he know that by the 1960s the success and profitability of the Guided Weapons Division, established after that meeting, would significantly helped to ensure the survival of the civil aircraft industry in Filton.

At that meeting the Bristol company was offered the chance to join with Ferranti, which had the electronics ability, to research into the production of a surface-to-air anti-aircraft guided weapon system, initially for ship protection. BAC gladly accepted and agreed to set up a team of their most able staff. The project would be led by David Farrar (below), a brilliant young engineer who had joined the company early in the war.